Varanasi is the holiest city for the Hindus of the world. Those who disagree with its being called the holiest will still not object to its being called one of the holiest cities. The city, tell the Hindu scriptures, has been central to the Hindu sacred geography since time immemorial. Its location by the holiest and divine river “Ganga” makes it very special: not only for the religious but also for the aesthetic purposes. The religious, and not so religious, people from all over the world come to Varanasi to wash their sins away. They believe that one dip in the holy Ganges will make them pure. It is also believed that dying in Varanasi frees one from the continuous cycle of deaths and rebirths. So, they come, throughout the year, in all seasons, to the ghats of Varanasi.

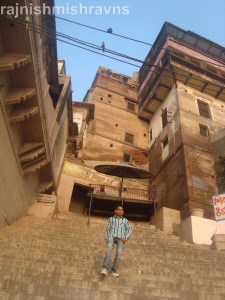

Aesthetically speaking, the ghats of Varanasi that stretch for around four kilometers along the western banks of the river provide a spectacular view under the sun and the moon both. People believe that the name of the city originates from its being situated between the confluences of the Ganges with two rivers: Varuna and Assi. Between the three rivers, then, is situated Varanasi. Although there are three rivers around the city, an unbroken series of stone ghats can be seen only by the Ganges.

Adi Keshav Ghat is right at the confluence of Ganga with Varuna. It’s one of the most ancient ghats of Varanasi and has the once very important but now forgotten by all but few, Adi Keshav Temple. Coming south wards, one reaches Raj Ghat upon which stands the famous road and railways bridge across the river: the Dufferin Bridge that’s now called Malviya Bridge. There are no pukka ghats between Adi Keshav and Raj Ghat. One has to walk over the dry alluvium and dense dots of human excreta. This zone is exceptional as it does not have crowds that generally occupy the pukka ghats of Kasi.

Near Raj Ghat is Rani Ghat, where one may see one of the most beautiful buildings on the riverfront: the white coloured house with a temple and many tenants. A narrow gali runs by the house and the stairs of various entrances of the house open into the gali. The ghats after Rani Ghat also have some beautiful buildings that speak about the period in which they were constructed. There are no significant ghats from there till Trilochan Ghat with its temple of Lord Shiva: the reigning deity of the city. Gai Ghat and Panchganga Ghat are the other well known ghats in these quarters.

Panchganga Ghat has been mentioned in various accounts of the travellers who came to Varanasi (that was called Benares then) during the Mughal period too because of its Bindu Madhav Temple where stands the Mosque of Aurangzebe now. It’s also known as Beni Madho ka Dharhara. It’s not just a coincidence that the old temple was popularly known as Beni Madho Temple and the mosque is known by a hybrid name that can be translated to “Beni Madho’s Steeple”. Now, steeples in a temple are not very common, and the mosque had been famous for its original steeple that had to be shortened because of its structural faults. The pre-Aurangzebe era temple equalled that of Vishweshwar in importance. Tavernier gives its detailed description:

I come to the pagoda of Benares, which, after that of Jagannàth, is the most famous in all India, with which it is even, as it were, on a par, being also built on the margin of the Ganges, and in the town of which it bears the name. The most remarkable thing about it is that from the door of the pagoda to the river there is a descent by stone steps, where there are at intervals platforms and small, rather dark, chambers, some of which serve as dwellings for the Brahmins and others as kitchens where they prepare their food.... The build- ing is in the figure of a cross, like all the other pagodas, having its four arms equal. In the middle a lofty dome rises like a kind of tower with many sides, which terminates in a point, and at the end of each arm of the cross another tower rises, which can be ascended from outside. Before reaching the top you meet several balconies and many niches, which project to intercept the fresh air ; and all over the tower there are figures in relief of various kinds of animals, which are rudely executed. Under this great dome, and exactly in the middle of the pagoda, there is an altar like a kind of table, of 7 to 8 feet in length, and 5 to 6 wide, with two steps in front, which serve as a footstool, and this footstool is covered by a beautiful tapestry, sometimes of silk and sometimes of gold and silk, according to the solemnity of the ceremony which is being celebrated. The altar is covered with gold or silver brocade, or some beautiful painted cloth. From outside the pagoda this altar faces you with the idols which are upon it ; for the women and girls must salute it from the outside, as they are not allowed to enter the pagoda, save only those of a certain tribe. Among the idols on the great altar there is one standing which is 5 or 6 feet in height ; neither the arms, legs, nor trunk are seen, the head and neck only being visible ; all the remainder of the body, down to the altar, is covered by a robe which increases in width below. Sometimes on its neck there is to be seen a rich chain of gold, rubies, pearls, or emeralds. This idol has been made in honour and after the likeness of Bainmadou, 1 who was formerly a great and holy personage among them, whose name they often have on their lips. On the right side of the altar there is also to be seen the figure of an animal, or rather of a chimera, seeing that it represents in part an elephant, in part a horse, and in part a mule. It is of massive gold, and is called Garou, 1 no person being allowed to approach it but the Brahmins. It is said to be the resemblance of the animal which this holy personage rode upon when he was in the world, and that he made long journeys on it, going about to see if the people were doing their duty and not injuring any one. At the entrance of the pagoda, between the principal door and the great altar, there is to the left a small altar, upon which an idol made of black marble is to be seen, seated, with the legs crossed, and about two feet high. When I was there it had near it, on the left, a small boy, who was son of the chief priest, and all the people who came there threw him pieces of taffeta, or brocaded cloth like handkerchiefs, with which he wiped the idol and then returned them to their owners. Others threw him chains made of beads like small nuts, which have a naturally sweet scent, which these idolaters wear on their necks and use to repeat their prayers over each bead. Others also throw chains of coral, others of yellow amber, others fruits and flowers. Finally, with everything which is thrown to the chief Brahmins child he wipes the idol and makes him kiss it, and after- wards, as I have just said, returns it to the people. This idol is called Morli Ram, 2 that is to say, the God Morli, brother of the idol on the great altar. Under the principal entrance of the pagoda one of the chief Brahmins is to be seen seated, close to whom is a large dish full of yellow pigment mixed with water. (JEAN BAPTISTE TAVERNIER's TRAVELS IN INDIA, 230-233)

Moving towards south, one crosses Scindia Ghat to reach the famous cremation ghat: Manikarnika. From there Dashshwamedh Ghat, the most famous ghat of Varanasi, is not very far. Some other important ghats are Kedar Ghat, Harishchandra Ghat, Hanuman Ghat, Shivalal Ghat, Tulsi Ghat and Assi Ghat.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.